Research

Elucidating the Origins of Eukaryote-like Chromatin Organization in Archaea

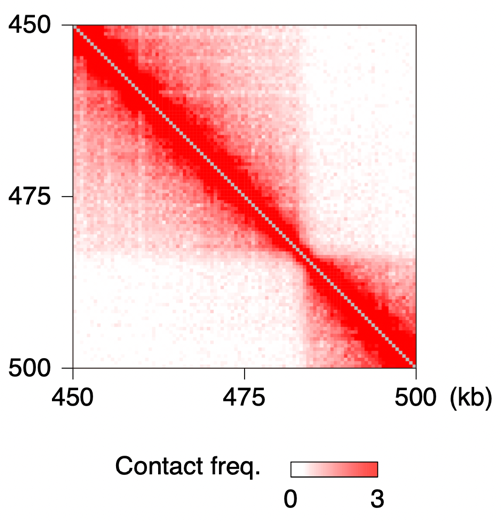

One of the most distinctive features of eukaryotes is their ability to organize the genome into a three-dimensional chromatin architecture. Chromatin is a fibrous complex primarily composed of nucleosome structures, where DNA wraps around histone proteins. These nucleosomes are further organized into higher-order structures—such as topologically associating domains (TADs) and DNA loops—through the action of various chromatin-associated factors, most notably the Structural Maintenance of Chromosomes (SMC) complexes. In eukaryotes, these structures are intricately regulated by numerous proteins, enabling precise control of genomic functions including transcription, replication, and repair.

To uncover how such eukaryotic chromatin originated, we study microorganisms known as archaea. Archaea are believed to be the prokaryotic ancestors of eukaryotes and possess homologs of key eukaryotic chromatin components, such as histones and SMC complexes. This suggests that archaeal genomes form chromatin-like assemblies resembling those present in the ancestors of modern eukotes. By integrating molecular genetics with next-generation sequencing (NGS)–based analyses, we aim to elucidate the structural and functional properties of this “archaeal chromatin” and thereby gain insights into the evolutionary origins of eukaryotic chromatin.

Our laboratory has pioneered the application of Hi-C/3C-seq—NGS-based methods for analyzing three-dimensional genome architecture—to hyperthermophilic archaea, enabling us to investigate archaeal genome organization and its functional implications (Takemata et al., Cell 2019; Takemata & Bell, Mol. Cell 2021). Currently, we focus in particular on the formation mechanisms and biological roles of TAD-like domain structures generated by archaeal SMC complexes (Yamaura et al., Nat. Commun. 2025). We have also expanded our research to archaeal histones. Although archaea form DNA–histone complexes similar to eukaryotic nucleosomes, their physiological roles remain poorly understood. Moreover, archaeal histones lack the intrinsically disordered “tails” that are essential for many functions of eukaryotic histones, and it remains unclear when and how these evolutionary differences emerged. Through functional analyses of archaeal histones and experimental evolution approaches in which eukaryotic histone tails are fused to archaeal histones, we aim to unravel the evolutionary trajectory of histone modifications and chromatin regulation.

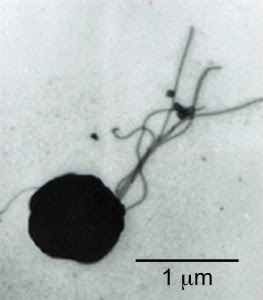

Hyperthermophilic Archaea: the primary model organisms of our laboratory

Thermococcus kodakarensis

Elucidating how hyperthermophilic archaea maintain chromatin functionality under extreme temperatures

Microorganisms with optimal growth temperatures above 80 °C are known as hyperthermophiles, many of which belong to the archaeal domain. Hyperthermophiles thrive in environments so hot that life would seem impossible, and have long fascinated researchers. However, many aspects of their biology remain poorly understood. In particular, how these organisms preserve the structural and functional integrity of chromatin under extreme temperatures—conditions that readily induce DNA denaturation and damage—has been a longstanding question.

Toward Applications of Archaeal Genomes

Archaea inhabit not only high-temperature environments but also a wide range of other extreme conditions. They also possess numerous unique metabolic pathways that are not found in other domains of life. These characteristics hold significant potential for future biotechnological applications. By elucidating the fundamental principles governing archaeal genome function—and by developing methods to manipulate and reprogram these systems—we aim to enhance and harness archaeal traits such as extreme-environment tolerance and distinctive metabolic capabilities.